| class_manage_sys_essentials_2.pdf | |

| File Size: | 687 kb |

| File Type: | |

| surface_management_techniques.pdf | |

| File Size: | 266 kb |

| File Type: | |

Behavior Management

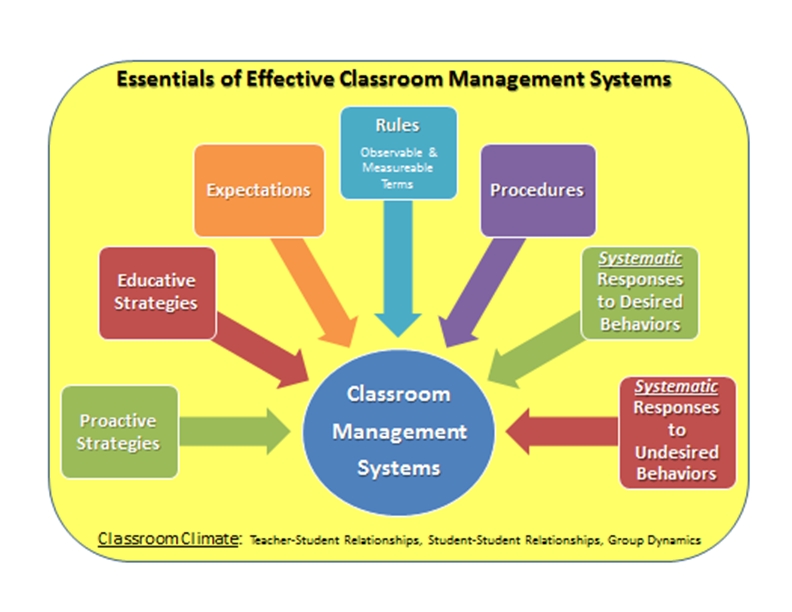

Effective behavior management requires attention to the physical environment, the curriculum, the schedule, the strengths and needs of the students, the strengths and needs of the teacher, and an understanding of foundational principles. The foundational principles described below are reprinted with the author's permission from Rockwell, S. (2006). You can't make me! From chaos to cooperation in the elementary classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. The free downloadable handout with definitions and examples of each of the components of Essentials for Effective Classroom Management depicted in the graphic organizer is available above, just under the graphic organizer.

Foundational Principle #1: The only person I can control is myself (Glasser, 1998).

Tara was an eight year old girl with a healthy set of lungs and vast quantities of misdirected energy. Her response to any request she believed to be unfair was to fall to the ground, scream, kick, and flail about like a beached whale. One beautiful, sunny day I took her and the rest of the class of students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) outside to enjoy a butterfly garden the middle school students had built for our enjoyment. Tara skipped down the mulch path hand-in-hand with her buddy George, a child of six with fetal alcohol syndrome and severe behavior problems. They loved finding bugs and lizards for our temporary classroom terrarium. When it was time to return to the classroom, Tara voiced her displeasure with a few grunts and foot stomps. I sensed a full blown tantrum on the horizon and sent the audience inside with Ms. Hill, our classroom aide. Tara opened her mouth to begin her customary wails and began to crumple at my feet just as a group of visiting administrators from the county office turned the corner of the sidewalk near our spot on the lawn. I knew from past experience that Tara would not respond to reason or reprimands. Neither rewards for good behavior nor punishment for bad behavior would abort her attempt to make a scene. Simply put, Tara had established through words and behaviors on many occasions that I could not make her behave. Wanting to spare myself and Tara the embarrassment of a public display of inappropriate, I whispered in her ear, “Tara, Sweetie, I know how you hate ants. Please don’t sit down here. There’s an ant pile over there in the grass.” With that said, Tara stood quickly, accepted my hand, and walked into the building without another word. I could not make her behave. I could only control my response to her behavior. By choosing wisely, I was able to assist her in gaining self-control. Over a period of 10 months, Tara did learn to respond appropriately to routine teacher requests without having staff resort to distraction, some other indirect technique of surface management, or physical restraint. The point of that anecdote, however, is not Tara’s talent for acting-out at inconvenient times. The lesson that Tara and others with behavior problems teach us is that in spite of our professional status, skills, training, degrees, and gifts, we are hopelessly powerless in the face of another’s noncompliance. Tara has more energy than the adults in her life, fewer time constraints than the staff, and the law on her side as a minor with a disability. She will win any battle that pits ugly behavior against ugly behavior. Adults just can’t out ugly the Tara’s of this world. The first and most important foundational understanding in the management of student behavior is the battle cry of all students with emotional and behavior disorders (EBD) in every school, “YOU CAN’T MAKE ME!” Our jobs, therefore, are not to force students into compliance, but to teach them self-control, self-reliance, and responsible self-determination. The only person I can control is myself. Surface management techniques that can come in handy in the moment are provided in the handout above (just under the explanation of the graphic organizer) titled Surface Management Techniques.

Foundational Principle #2: Behavior is purposeful (Glasser, 1998; Alberto & Troutman (1990).

Think about something you liked to do as a child. Jot 2 or 3 ideas down before you read the next paragraph.

Did you enjoy those activities enough as a child that you still do them when you can, even if you have modified them to meet your present level of functioning?

Did you enjoy those activities enough as a child that you taught your own children or children you love to engage in them?

After all of these years, what brings you back to those activities? What need or needs do those activities fulfill for you?

When I ask folks to share their thoughts on these questions during workshops, I am often told that people enjoyed riding a bike, visiting with extended family or grandparents, and playing outside with friends. They report that they still enjoy some or all of the activities listed and encourage the children in their lives to participate as well. As they explore the needs satisfied by the activities discussed, they mention a feeling of freedom, belonging, love, fun, and basic needs such as food and rest.

Consider these questions as a follow-up to the pleasant memories. What activities did you dislike as a child?

With the exception of life sustaining chores that are required of responsible adults such as yourself, do you participate in the activities you disliked as a child now that you have a choice?

What did you do when adults in your life attempted to make you participate in those activities?

Workshop participants often mention household chores such as washing dishes or ironing clothes, practicing a musical instrument, or going to bed at a specified time. They laugh openly as they share ways that they used to try to trick their parents into thinking they had done the required task or avoid being compliant in some other way. Whining, crying, pretending to be too sick or too tired, hiding a flashlight under the blankets, and suddenly needing to go to the bathroom are the most frequently reported avoidance tactics. Some folks report hating their chores so much that they have purchased labor saving devices or hired others to do the work they were once required to do.

Now, think about the ways students with behavior problems attempt to avoid following directions in your class or at your school.

Are their behaviors radically different from yours or those of your friends?

Behaviorists have determined through stringent research studies that behavior serves a function. People work to get or avoid attention, tangible items, and activities. Unraveling the behavioral sequences, environmental contributors, and particular needs of a specific group or individual can be time consuming and mind boggling. In the end, however, a successful resolution is always worth the time and effort.

Students with challenging behaviors engage in noncompliant behaviors more frequently and with more passion than other children, but are often not terribly different in terms of methods or motives. Our children with challenging behaviors are attempting to either fulfill a need or want or avoid something they believe to be aversive. Their behavior, however misdirected, is their best attempt at that moment to communicate a want or need. Sometimes their behaviors are so contradictory on the surface that we have trouble understanding what it is that they are trying to tell us. Jeremy’s story in the next section illustrates the

purposefulness of behavior, the complexity of the behavioral message, and the power of success.

Principle # 3: Reinforcement increases the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated. People are attracted to objects, activities, and others who are reinforcing (Glasser, 1998; Alberto & Troutman, 1990).

Jeremy bounded into the classroom as if propelled by invisible jets. He talked non-stop and ran from one desk to the next, slapping table tops, kicking chair legs, and snatching other students’ work from their hands. Greased lightning would have been easier to contain. My associate and I looked at each other in momentary stunned silence. Most of the students in this fourth grade class were academically capable and quick to use their fists to settle a disagreement. Jeremy had a borderline IQ, a history of physical abuse and neglect, few social skills, and the attention span of a gnat. For his protection, we had to find a way to engage him academically and behaviorally. His classmates were not going to tolerate his talents for disruption.

During lunch, I read his files. According to the child study team, Jeremy hated to read, write, complete math worksheets, or engage in anything remotely educational. Previous attempts to establish contracts, reinforcement schedules, and aversive consequences for noncompliance had failed. His chronological age was 9. I roughly estimated his mental age to be about 6. His expressive language skills and academic levels were more typical of a 3 to 4 year old. Socially and emotionally, he appeared to be even younger. Children like Jeremy had always intrigued me. As I watched him fight his way through the day I wondered what had happened to the precious baby boy he once had been. How can a teacher address the infantile needs of a 9 year old for touch, protective boundaries, mirroring, and attention? Ms. Haines, the associate, and I decided to attempt to meet Jeremy’s needs for attention and touch in an age appropriate manner by rubbing his back, touching his shoulder, shaking his hand, rubbing his head, and engaging him in a high five every 3 minutes throughout the day. As long as one of us got to him within a 3 minute time period, Jeremy remained in his desk and completed simple academic tasks. His fine motor skills were very poor. Because of this, we modified assignments and engaged him in a variety of activities designed to strengthen motor control while simultaneously addressing academic skills such as sound-letter correspondence, place value, and word recognition. Attention to Jeremy’s developmental ages across various domains made it easier to design successful interventions. Within the second week of our reinforcement program, Jeremy was able to remain in his seat and on task with 5 minute intervals between physical touch. By the end of his first month with us, he was able to work for 20 minutes at a time. He made adequate academic progress that year, but the most striking changes in him were behavioral. He was able to play simple games with peers, participate in group lessons, and contribute positively to the class. Getting a reluctant student to read, write, or stop hitting others requires careful attention to what reinforces that child. People are not successful because they do more. People do more because they are successful (Katz, 1999).

Foundational Principle #4: Punishment decreases the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated. People avoid activities, objects, and other people they believe to be punishing (Glasser, 1998; Alberto & Troutman, 1990).

Behaviorists have known for many decades that punishment delivered immediately and with sufficient intensity stops a behavior from occurring. Punishment does not, however, teach a replacement behavior. In the movie, The Truman Show, the main character, Truman, wants to get off the island where he lives to find a woman he loves. He was taught to be afraid of the water when he was a boy by being caught in a storm and being made to believe that he was partially responsible for his father’s death. In spite of his great fear, he finds a sailboat and sets off on his journey. The director of the Truman television show does not want Truman to escape. He has the special effects technician increase the intensity of the storm. Winds whip the boat. Lightning strikes close to the boat. Truman hangs on to the mast and screams, “Is that the best you can do? You’re going to have to kill me!” Truman continued even after two attempts were made to frighten him into returning to the island by nearly drowning him. He needed to get to the woman he loved. Death was an acceptable price to pay for trying. As I watched that movie for the first time I thought about all the children who had told me over the years that they would persist in their disruptive, noncompliant behavior to the death if pushed by adults to go that far. The more youth with behavior problems test our patience and good will, the more willing we often become to strike back—to attempt to make them behave with force and punishment. Many of them become immune to adult threats even before they are old enough to attend school. Of what consequence is a time-out room to a child who has had both legs broken at the age of three by a step-parent? How punishing can the school be to a child who has been raped repeatedly by a family member? For children who are called degrading names and slapped across the head and face, our contrived punishments are a joke. It is no wonder that they laugh at us. The most difficult foundational principle for many folks to understand is the first one about having control only over our own actions. The second most difficult foundational principle for many folks is this one. Punishment is too often a weak and meaningless exercise of power in artificially contrived school settings. Punishment does not teach a new behavior, inspire compliance, or encourage the student to engage with us. For our most challenging students, punishment should be a last resort simply because we have so little with which to bargain in the beginning. We must have something positive to offer them before the removal of that positive, reinforcing object, person, or activity will be meaningful. In addition to the limitations of punishment given students’ life experiences beyond the school, punishment does not teach a desired behavior. For the student’s safety as well as the safety of others, we have a responsibility to remove aggressive, disruptive students from a situation until they regain control. That should not be confused with punishment. Too often adults think they are punishing a child when, in fact, they are rewarding the child by allowing them to avoid a task they dislike or giving them the attention they crave during the time away from class.

Foundational Principle #5: All people have the same basic needs (Glasser, 1998).

In the 60s Maslow proposed a theory of motivation that included levels of need. He believed that one level of need must be satisfied before people would be motivated to move to the next level of need. The medical community still uses Maslow’s (1962) hierarchy as an informal assessment of patients’ moods and attitudes toward treatment in hospital settings. Glasser (1998) identifies 5 basic human needs. While survival is a necessary prerequisite to achieving the other needs, he proposes a model that is more connected to the setting in terms of need fulfillment. The other 4 needs that Glasser proposes are (a) love, (b) power, (c) freedom, and (d) fun. Driekurs, Grumwald, and Pepper (1982) identified motivations for misbehavior as (a) a need for power, (b) a need for revenge, (c) a need for fun, and (d) a need for assistance or attention satisfied through feigned helplessness. Behaviorists such as Alberto and Troutman (1990) identify motivation for behavior in terms of actions that assist the student in gaining or avoiding objects, attention, sensory stimulation, or activities. Time and energy could be spent arguing the merits of a strict behavioral approach that ignores the cognitive and emotional components of motivation and behavior. The fact remains, however, that regardless of the model from which an educator identifies motivations for behavior, students who exhibit more than their share of behavior problems are working to meet the same needs as students who have learned to comply with classroom, school, and social rules. Tara tended to fall on the ground and scream when she wanted to continue an activity she preferred. Glasser (1998) would describe Tara’s quality world or cognitive picture of a good day as containing only a limited number of tasks and people in the beginning. He would probably suggest that changing Tara’s behavior should include opportunities for her to broaden her interests, relationships with others, and skills across different domains. Alberto and Troutman would probably focus on Tara’s skill deficits in communicating her needs and her performance deficits in making successful transitions. Tara would be taught to express her needs verbally and would be reinforced when she successfully communicated and transitioned from one activity to another. The point of this foundational principle is that students with behavioral challenges are more like others than different from others. Correctly identifying a student’s need or a group’s need is essential to selecting the most effective intervention.

The events and behaviors exhibited by the following class of students illustrate the power of need identification in addressing problem behaviors. Ms. Lambert came to me one day to discuss unexpected changes in her class. For the first nine weeks of school, they had been well behaved and exceptionally productive compared to other classes she had had in the past. Over a 3 week period of time, however, their behavior problems had increased. The principal called her in to discuss the number of office referrals she had written. In addition, progress reports would be sent home in another week and a half. She dreaded the parents’ reactions when they saw the decline in achievement. As we talked, it became apparent that the class was reaching a peak of noncompliant, off-task behavior right before lunch. I asked her if anything had changed with regard to her schedule. She reported that because of over-crowding in the cafeteria and at physical education (PE) her class was now attending lunch 45 minutes later than usual and was going to PE during the first hour of school. We knew that many of the students were not eating a proper breakfast and hypothesized that the late lunch combined with an early PE was leaving them feeling hungry. At my suggestion she sent a note to parents requesting that the students bring a healthy snack to school. When the students returned from PE, they were allowed to eat their snacks while the teacher read a story. Behavior problems decreased immediately and dramatically. Work production increased immediately and dramatically. Neither Ms. Lambert nor I had ever been quite as successful at pinpointing and resolving a problem before this time, but were thrilled with the results. Too often teachers begin by establishing a complex behavior management system with tokens, hierarchies of punishment, and other strategies when the problem is more basic and more easily addressed once the students’ needs are identified.

Foundational Principle #6: Each person has his or her own belief about how to meet a particular need (Glasser, 1998).

Take an imaginary journey with me for a moment. Pretend that you had been notified of a prize package that included luxury accommodations at a 4 star hotel. You were promised a manicure, pedicure, massage, facial, and unlimited access to all amenities. A limousine picked you up at your door and the chauffeur told you to leave all of your personal belongings behind. You have been promised a completely new wardrobe at no cost to you. You crawled into the backseat of limo, turned on your favorite music station, and enjoyed a beverage of your choice while someone else took care of all the details. When you arrived at the surprise location, the chauffer opened the door to reveal a panoramic view of mountains, streams, rapids, and waterfalls. You were completely amazed!

Then the chauffeur walked you to the door of a cabin, said, “Have a great vacation.” and left. Clothing, food, and other supplies were available in the cabin. It even had a vibrating chair. Under different circumstances, you might be thrilled to have 2 weeks to relax, read, explore the wilderness, and contemplate the meaning of life. Given your expectations prior to arriving, however, you are miserable. Why?

Our ideas of how to best meet our needs have developed over the course of our life times. Before we were able to make our own decisions, our families introduced us to some options. As we grew, we rejected some of those early choices and added new ones. A child’s prior experiences, areas of strength or skill, deficits, and temperament will interact to create his or her personal beliefs about how to best meet his or her needs. When children are very young and dependent upon the environment, they will tend to react to more immediate events. As the children gain in cognitive ability, they will bring more of their own agenda to the present experience. People, activities, objects, and types of sensory stimulation that have pleased them in the past will be sought in the present and the future. People, activities, objects, and types of sensory stimulation that have been unpleasant for them in the past will tend to be avoided in the present and the future. Children who have experienced failure and rejection during their early experiences with school are at great risk for developing negative beliefs about (a) their own abilities to learn, (b) the value of attempting to make friends and participate in school related activities, (c) the trustworthiness of the adult authority figures in school environments, and (d) their abilities to positively impact the overwhelming odds they perceive to exist in the classroom. One of the biggest hurdles I face when I work with children who have experienced on-going school failure is convincing them that school can be a pleasant place to be. The second biggest hurdle is convincing them that they are capable of achieving.

People sometimes think that children are not affected by their thoughts and beliefs because of the immediacy of their response to the environment. Seligman (1995) reports that children as young as 7 develop thinking patterns clearly oriented toward learned helplessness or learned optimism. One little nine year old I worked with several years ago exhibited frequent acts of physical aggression. He would throw furniture, hit, kick, scratch, bite, and destroy instructional materials when he became angry. Early in our year of working together he told me that he could not help being violent. He explained that his Daddy was in prison for hurting people. When Carson became angry and aggressive at home, family members told him he was just like his Dad. One day after a particularly nasty tantrum, I talked with Carson about his choices. He had been making tremendous progress academically. He was beginning to believe that he could achieve school success in reading, writing, and math. As I held his hands, his little body shook with the last sniffles and tears of his outburst. I asked him what he was thinking. Tears rolled down both beautiful cheeks as he slowly choked out, “I’m afraid.”

“Carson, what frightens you?”

“I’m afraid that I will go to prison like my Daddy. I want to be good, but I’m afraid that I can’t be.”

My response was clear, firm, and direct. “Carson, look at me.” His gaze slowly moved from the carpet to meet mine. “You decide who you will be. You know that you are smart. You know you have made great progress already in your school work.” Carson nodded affirmatively. “Remember this, young man, if you remember nothing else. You decide who you will be—not your Daddy—not your Mom—not your Grandma. All of us, including your Daddy, want you to be successful. We care about you and want to help you. But, you decide who you will be.”

Carson still had problems with violent behavior from time to time after our talk. His ability to self-manage increased, however. By the end of the following school year, he had attained grade level achievement across subject areas and had learned to talk to a trusted adult when he was angry instead of taking his anger out on the environment. The last news I had of Carson was that he played football for his high school team and had earned a scholarship to college. Before Carson received corrective experiences, he believed that school was a place to fail and to fight. He believed that he had little chance of being successful. He could not read or spell. His Dad was in prison. His family told him that he was headed to prison like his Dad. What reason did he have to work hard, manage the inevitable frustration of the learning process, and trust adults who were too stupid to understand that he was already doomed to life of crime? The context of a problem includes the setting, events in the setting that occur before and after a problem, people involved in the setting, and the thoughts of the person who is targeted for intervention. Foundational Principle #7 addresses three basic assumptions from which successful people operate.

Foundational Principle #7: People who have had needs met reliably through socially accepted means operate from 3 basic assumptions (Janoff-Bulman, 1992): (a) We live in a benevolent and just world, (b) life has meaning, and (c) we are worthy.

Marian Wright Edelman (1992) describes her early years as being supportive of her growing belief in her ability to achieve and contribute to her community. In spite of factors in her life that might be perceived by others as creating a level of risk for her and her siblings, she persevered. She learned by example and through direct interaction with significant adults that while the world was not entirely safe or just, there were reasons to believe that benevolence and justice were qualities worth championing. She learned that life has great meaning, and that an understanding of that meaning was a call to action. She also learned that she was worthy—indeed, that all people are worthy. Her early experiences with people who reliably met her needs fostered a deep and abiding faith that has continued to propel her into action on behalf of others who are less fortunate. In her own words, she describes how this process unfolded for her.

I was 14 years old the night my Daddy died. He had holes in

his shoes but two children out of college, one in college, another in

divinity school, and a vision he was able to convey to me as he lay

dying in an ambulance that I, a young Black girl, could be and do

anything; that race and gender are shadows; and that character, self-

discipline, determination, attitude, and service are the substance of life.

I have always believed that I could help change the world

because I have been lucky to have adults around me who did—in small

and large ways. Most people were of simple grace who understood

what Walter Percy wrote: You can get all A’s and still flunk life. Giving

up and ‘burnout’ were not part of the language of my elders. You got up

every morning and did what you had to do and you got up every time you

fell down and tried as many times as you had to get it done right. They had grit (Edelman, 1992, pp. 7-8).

It is clear from Edelman’s brief description of her early years that protective and supportive structures surrounded her from her first beginnings. She reports feeling loved and challenged through multiple experiences with family, friends, and community members. While she faced many hardships and obstacles, her earliest beliefs about herself reflected those of the adults who surrounded her with high expectations, an unwavering sense of hope for her and for the world at large, and an honest appraisal of what it would take to succeed. Her sense of personal and interpersonal responsibility as an adult was built upon those childhood messages, experiences, and beliefs. Many students who exhibit problem behaviors have not had such protective, predictable, supportive care. Trauma and repeated exposure to threat or failure can erode a child’s belief in self and others. Understanding the cognitive components that underlie overt behavior is important in designing effective interventions.

Foundational Principle #8: Trauma shatters those assumptions (Terr, 1990; Katz, 1997; Seligman, 1995; Janoff-Bulman, 1992). Chronic and long-term exposure to failure can erode a person’s belief in those assumptions as well (Katz, 1997; Seligman, 1995).

As students grow, they add more experiences to the life stories they construct (Singer & Salovey, 1993; Wood, 1996). If the majority of their experiences have been unproductive, they carry a set of beliefs with them that actively work against more direct efforts to teach social skills and manage surface behavior (Seligman, 1995; Wood, 1996; Kendall, 1991). In contrast to Edelman’s story and as an illustration of the power of children’s beliefs in the maintenance of their behaviors, an experience with a group of 4th and 5th grade boys with EBD is offered.

All of the boys in this class lived with parents who were either addicted to drugs or engaged in illegal activities. They told me often about shootings at night in their neighborhoods. According to them, all of the children who lived in their area went inside at dusk to play games or watch television. They remained flat on the floor each evening to escape bullets that might hit them from drive-by shootings. One child had watched his mother die when he was 5 years old. His stepfather had chopped off his mother’s arms. It took several hours for the police to talk the man into releasing the children. Another boy in the class had witnessed a violent attack by his mother on his father’s pregnant girlfriend. The mother came home to find the father having sexual relations with the girlfriend in the master bedroom. The mother went to the kitchen, returned with a butcher knife, and stabbed the pregnant woman in the abdomen. The baby died.

I repeatedly attempted to discuss the benefits of maintaining a nonviolent classroom with this group. I told them that fighting was not a responsible way to handle anger and conflicts, but they had plenty to tell me about the subject! They told me about their lack of trust, their need to defend not only their honor, but also their very existence. They challenged me to live just one day in their shoes. They were only 10 and 11 years old. In spite of my determination to run a safe and trustworthy program, they persisted in seeing danger and reasons for aggression at every turn. They cursed, threw furniture, smashed windows and other school property, and resorted to a group brawl on the lawn in front of the classroom on more than one occasion. They were so determined to prove to me that might is right.

While I could not totally change those beliefs in the short period of one school year, we did eventually establish a peaceful classroom. They learned to be responsible within the four protected walls of our environment. We cooked, read, wrote books, built model towns, sang, and talked. Our book and model town were placed on display in the school office. Our treats were shared with staff and other classes. We established a community of mutual respect, trust, and care that allowed those young men to be responsible with me and with each other. In order to accomplish that, multiple experiences over a period of months were developed to satisfy their needs for safety, trust, nurturing, protective and supportive boundaries, achievement, choices, and service to others.

Neither a behavior-management system nor a series of social skills lessons alone would have been enough. The students need to be heard. And I needed to know what they were thinking. I could not even imagine living in such a terrifying environment. Even if they embellished some of the details and were less than accurate at times about all that they reported, their beliefs about themselves and others came through in our discussions. By listening to their stories, I gained a better understanding of how to meet their needs in ways that would make sense to them. They needed the same things that we all need—to feel safe, valued, strong, capable, and worthy. When past experiences have not lead to socially acceptable methods for meeting those needs, however, teaching personal and interpersonal responsibility is a tremendous challenge.

I’d like to pretend that I began the year in that classroom with a clearly defined plan. The reality is, I did not. The students’ propensity to interpret every action as a threat was as wearing as it was disturbing. This group of children required diligently enforced controls on all acts of aggression within a structure that protected their needs to see themselves as strong and independent. I drew large boxes on the floor around their desks with chalk. Time-out was immediately enforced for any movement that extended out of their assigned areas. Academic work was carefully structured for success. Anytime a student said, “I can’t do this,” I replied, “I will never ask you to do anything that can’t be done. Tell me what you know. We’ll go from there together.” Daily routines included negotiable and non-negotiable items. A sense of power and control can be enhanced through opportunities to make choices and give suggestions. In spite of their limited abilities in the beginning to make responsible choices and provide appropriate input, carefully structured academic and affective lessons were offered that elicited such responses.

Independent work was often assigned with a group project in mind. In the beginning, working together was impossible. Working alone to contribute to a class product allowed the students the safety and sense of accomplishment they needed while encouraging them to take pride in group membership. As projects took shape, they were shared with the larger community of the school. Students received positive feedback from other teachers, administrators, and peers. Family members were encouraged to visit as well. Being strong, capable, and worthy extended beyond the ability to fight. Power, control, and achievement were possible through school appropriate behaviors. The group was finally able to function peacefully. I no longer drew boxes on the floor around their desks. They did not give up their belief that the world beyond the classroom was a threatening place. They still believed in violence. However, new choices were added to their repertoire and practiced daily, though it must be said that the new did not by any stretch of the imagination erase the old.

When one of the students was asked at the end of the school year what he had liked about the class, he said that the teacher did not want to talk about what he could not do—only what he could do. Students with behavioral challenges are often too aware of what they cannot do. Empowering them to become responsible members of a class, school, and community requires a balancing of their needs for attachment versus independence, autonomy versus external control, and initiative versus destruction or apathy.

Foundational Priniciple #9: Human beings strive to remain in control (Terr, 1990).

The group of students described in the previous section used violence as their primary method for maintaining control of any situation they disliked or distrusted. Other students quietly refuse to comply with routine expectations, curse, run away, or are truant. As early as the age of 18 months to 2 years, children will exercise control over eating, drinking, and elimination. The drive to be independent is a double-edged sword. Educators and parents want children to self-manage, self-regulate, and self-evaluate as long as the children decide to comply. If children decide to follow their own agenda—one that is at odds with the adults in their lives—power struggles begin. Foundational Principle #1 states that the only person one can control is oneself (Glasser, 1998). Our need to feel as if we have some control over our lives is essential to our mental health (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Seligman, 1995; Glasser, 1998; Terr, 1990). Adults tend to attempt to take control away from students who refuse to comply. This increases the students’ levels of tension which intensifies their commitment to non-compliant behavior. The power struggle cycles (Wood & Long, 1991) and spins out of control unless someone with an understanding of the process intercedes. Jordan’s story revealed in the next section clearly illustrates his need to remain in control and how a sense of shame intensified his motivation to act in undesirable ways. In any given situation, the adult has a choice—to model respect for the individual and self, or to model the emotion acted out in the child’s behavior. A student walks into the room, throws his backpack on the floor, and screams, “Shut-up, you son-of-a-b___!” when the teacher asks him to pick up the backpack. The teacher can scream, “You can’t talk to me that way! I won’t have it.” and write a discipline referral; or the teacher can quietly walk closer to the student and say, “I see that this is a tough morning for you. I’m sorry that you are not happy. Please tell me how you feel without screaming and using inappropriate language.” The first teacher response models the level of disrespect and anger the child exhibited. The child has little to lose at this point and will probably escalate. Since the law, professional ethics, and good sense places a limit on how far the teacher can escalate, the student will win in his own mind if the teacher continues down this path. The second response will probably be unexpected. The element of surprise alone might be enough to get the student’s attention the first time a teacher tries it. The advantage to the second teacher response is that it allows the student to save face, remain in control, and make a decision. The student is not backed into a corner where he will feel that lashing out is his only choice. Jordan provides an even more complicated scenario related to control with an added level of shame that many students with behavior problems feel even though they rarely reveal it openly.

Foundational Principle #10: Shame comes from public exposure of one’s own vulnerability. When others ‘know’ that you once were helpless (or continue to be helpless in some way), you tend to feel ashamed. They know (Terr, p. 113, 1990). Human beings work to avoid feeling shamed.

Jordan has a medical problem. His bowels leak feces—especially when he becomes anxious. Four operations failed to correct the inherited condition that causes his chronic incoprecis. Jordan is understandably distressed by this disorder. Until a successful intervention was conducted at school, other kids wouldn’t play with him. They marked his seat with foul names and refused to sit near him. If one of his classmates was asked to sit in a chair that Jordan had used, the whole group erupted with taunts. To make matters even worse, Jordan refused to change his clothes when he had an accident. The stench in the classroom was unbearable and only invited further ridicule from his peers. He was 9 years old. The teacher could not make him change clothes. He was too big and too old for a female teacher to wrestle to the ground, strip, sanitize, and dress. Over the feigned gagging, screams of laughter and ugly names that Jordan’s peers called out could be heard Jordan’s shrill and insistent refrain, “I’m not changing my clothes, and YOU CAN’T MAKE ME!”

Jordan had been offered rewards for changing his clothes and endured punishments for refusing to change his clothes. His mother was beside herself with embarrassment and had all but given up on trying to help him. School officials were fearful of the health issues related to human waste products and were tired of the on-going, daily battles Jordan created with his refusal to take responsibility for his actions. Jordan attended a public school and was assigned to a self-contained class for students with EBD. His academic achievement had suffered slightly due to hospitalizations and frequent refusals to follow directions when in school, but he is capable of learning.

I watched Jordan’s daily battles from afar the year he was in second grade. When he was assigned to me for his third grade year, I talked with him and his mother. I found out that when Jordan was fully grown the doctors would be able to operate again. The success rate with adults who have his condition is over 90%. His physical problems would be over in 8-10 years. Unless we were successful soon; however, his social, emotional, and behavioral problems would be out of control by then. With Mom’s knowledge and permission, I decided to move beyond (a) attempting to keep Jordan calm to help him avoid an accident, (b) rewarding him for changing his clothes when he had an accident, and (c) punishing him for refusing to change his clothes when he had an accident. I asked Jordan what he was thinking when he refused to change his clothes. He told me that he was afraid that the other students would tease him more. He said that if he changed his clothes, they would know he had had an accident. I couldn’t convince him that the smell was proof enough of an accident. On a hunch, I asked him if he was mad at the kids for making fun of him. He began to cry and shook his head in affirmation.

“Jordan, could it be that you are trying to punish them?”

“What do you mean?” he asked through sniffles and tears.

“Well, you know that it stinks when you have an accident. I was just wondering if you were mad at the kids for teasing you. Making them suffer with you might be a way of punishing them.”

“Yeah, I do get mad. So what if they have to smell it!”

“What if they didn’t tease you any more? Would you still want to punish them?”

Jordan began to cry again. “I just want somebody to like me. I can’t help it if I have this problem. It isn’t fair. It just isn’t fair.”

“I agree, Sweetie. It isn’t fair. Would you be willing to talk with the class?”

“No WAY! They’ll just tease me even more.”

“I don’t think they will. I think if they understood everything, they might act differently. Besides, it’s worth a try.

What if I stood behind you while you talked and made sure that no one teased you? Would you be willing to tell the students about your operations and all the medical reasons for your problem?”

“I guess so.”

“When you finish telling them, I’ll want them to talk with you about how they feel. I won’t let anyone be mean to you, though. O.K.?”

“O.K.”

Later that day, I placed the students’ chairs in a semi-circle. Jordan sat in the center with me behind him. I explained the ground rules for the class meeting before Jordan started.

1. Only talk about yourself—your thoughts, your feelings.

2. No name calling.

3. No teasing.

4. Anyone who violated a ground rule would be removed from the group immediately.

Jordan told his medical story. The students were amazed. They had no idea that he had suffered so much pain. They asked insightful and sensitive questions about his experiences in the hospital and wanted to know if the doctors would ever be able to help him. He was quite knowledgeable. With quiet confidence and surprising competence he answered all of their questions. When he was finished, I asked his classmates to talk with him about how they feel when he refuses to change his clothes.

“No offense, Man, but it really stinks.” said Jose.

“Yeah, we’re sorry about your medical condition. We didn’t know. We thought you were just being mean to us.” added Marcus.

“Why do you do that, Jordan?” asked Janine.

“I was afraid you’d tease me even more if I changed my clothes.”

The discussion continued. The class offered to be friends with Jordan and stop teasing him in return for his cooperation when accidents occurred. At the end of the group meeting, several students spontaneously hugged Jordan, others asked him to sit at their table during lunch. Within a short period of time, Jordan was taking responsibility for more than his medical condition. He was mainstreamed back into a general education classroom and never returned to full time placement in special education classes again.

Jordan’s story illustrates the power of understanding the purpose of a particular behavior. Jordan wanted friends, was angry that his peers made fun of him for something he could not entirely control, and felt deeply ashamed of his inability to control his bowel movements. His peers were angry with Jordan, because they thought he could control the medical problem. Jordan was punishing his classmates for their mean comments and simultaneously attempting to avoid the shame and embarrassment that he felt. Jordan’s classmates were punishing Jordan for soiling his pants. Once they communicated their thoughts and feelings they were able to develop a plan that worked well for all of them. Behavioral strategies designed to reward and punish the class and Jordan were doomed to fail. Third graders are not going to forgive another third grader for soiling his pants and refusing to change them no matter how big the punishment or reward might be. Jordan wanted and needed friends. He felt that he had no way of making friends given his medical condition. No reward or punishment offered by the school could over-come his anger, loneliness, shame, and despair. Thoughts and emotions become increasingly powerful factors in the behavior of students as they become older and more able to plan ahead, self-evaluate, and assess the people with whom they interact. Beliefs and attributions may not be directly observable, but are important factors in addressing the behavioral and emotional needs of older, higher functioning students.

Foundational Principle #11: The four components of behavior are (a) overt, observable behaviors, (b) thoughts, (c) emotions, and (d) physiological reactions (Glasser, 1998). Interventions need to address all four components of behavior.

A former student named, Sammy, illustrates the importance of understanding the physiological, behavioral, ecological, and cognitive factors contribute to overt behavior. Sammy was a 7 year old who had just been released from a community-based psychiatric facility in another community. A social worker stopped by my classroom the day before his arrival to give me a brief description of his case. He was placed in the custody of his grandparents at the age of 6 months due to severe neglect. His mother had abused drugs while pregnant with him. He did not smile for several months and had frequent, violent, and unprovoked tantrums. The grandparents sought professional help when he began at the age of 4 to verbalize his intent to kill animals and people. The incident that prompted his referral to the psychiatric facility was Sammy’s attempt to kill his grandparents while they slept by setting the house on fire. He scored in the gifted range on individually administered intelligence tests, so his inability to act responsibly was not a function of poor cognitive skills.

On that first Tuesday morning, he greeted me politely and participated calmly and appropriately in class activities for the first 2 hours. Then without warning or noticeable provocation, he began violently banding his head on a brick wall, scraping his face with his fingernails, and smashing any materials within his reach. His screams were ear-splitting. I sent my aide to another room with the rest of the class and attempted to calm him. Some of Sammy’s problems were related to temperament and other biological factors and some were learned behaviors. He had frightened people often enough in the past to know that certain behaviors sometimes achieved a useful purpose—people demanded less out of him and gave him more of what he wanted. In addition to learned and biologically controlled responses, Sammy exhibited advanced cognitive abilities. While this was helpful in redirecting Sammy’s energy to more productive, achievement-oriented academic goals, it also worked against him in establishing peer relationships in other situations. The environment of a self-contained classroom provided him with the structure and safety he needed through clearly defined limits, immediate consequences, predictable and balanced scheduling of activities, social skills instruction, and academic tasks modified for his level of cognitive functioning.

As he required less external support, expectations for his participation in problem-solving sessions and cooperative learning activities increased. Sammy began to ask permission to visit the media center and general education classrooms unattended. He made friends with peers in other classes and was a welcome member of the school community. His grandparents reported that he was also making excellent progress at home, in counseling, and in community-based youth programs. Collaborative, developmentally sensitive, and individually modified interventions helped Sammy gain new skills and reframe his beliefs about himself and those around him. School, friends, family, and neighborhood experiences became increasingly reinforcing. Sammy was well on his way to developing the personal and interpersonal skills necessary for living a healthy, productive life.

Foundational Principle #12: What is done TO, FOR, and WITH youth has powerful, long-term effects.

I am struck regularly by the mechanistic approach we use to help youth self-right. We too often observe, take data, analyze data, hypothesize about the child’s needs or wants, design interventions, implement interventions, and make further decisions about programming without even consulting the child. We try to ‘fix’ the child, the classroom group, and the family without looking at more than the surface variables. The more we do things TO children and FOR children, the less responsibility they take for their actions. We have a responsibility to take care of our young people. That of course will include providing them with food and shelter and directly teaching them the academic and behavioral lessons our society expects them to learn. What we must never forget, however, is that while we are doing TO them and FOR them they are learning about who we think they are and who they expect they will become. The unspoken messages sent during our attempts to control and to protect are as powerful as the direct lessons we teach.

Children learn best when we do things with them—when we model the behaviors we want them to emulate—when we provide them with carefully scaffolded opportunities to make age-appropriate decisions—when we do not shelter them from the natural and logical consequences of their choices, but believe in them even when they experience a momentary setback. Teaching is more than the sum of its parts.

Carson believed that he was doomed to a life of crime because of what his mother and other family members told him. He did have a difficult temperament as a baby and a quick temper as a young boy. His future, however, was not predetermined by his genes, his socio-economic status, his race, or his gender. He had within him the abilities, even at his young age, to self-select the people he would emulate, self-regulate his actions to a degree, and self-evaluate the appropriateness of those actions. One of our most important roles for youth like Carson is to be a positively distorted mirror that reflects back to them not who they are at the moment, but who they can be. Carson learned through interactions with many people that he had choices. He could give up on himself and give in to the aggressive impulses he felt, or he could learn to manage his temper and succeed. With support at home, in the community, and at school, he did indeed succeed.

This last foundational principle is critical because we too often forget to do things WITH the most challenging children. We are tired and frustrated. We just want the disruptive behavior to stop, so we focus on that. As long as we focus on the “bad” behavior, the students will also put their energies there. Engaging them with us in academic success, affective education, the arts, physical education, and the rich array of productive options available helps them to redirect their energies, emulate more positive models, and begin to see themselves as worthy of more than they had ever dreamed.

References

Alberto, P.A., & Troutman, A. C. (1990). Applied behavior analysis for teachers: Influencing student performance (5th edition). Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company.

Alberto, P.A., & Troutman, A. C. (2002). Applied behavior analysis for teachers: Influencing student performance (6th edition). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Edelman, M. W. (1992). The measure of success: A letter to my children and yours. Boston, MA: Beacon Publishing.

Glasser, W. (1998). Choice theory. NY: Harper Perennial.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1993). Shattered assumptions. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Katz, M. (1999). On playing a poor hand well: Insights from the lives of those who have overcome childhood risks and adversities. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Seligman, M. (1995). The optimistic child. NY: Harper Perennial.

Terr, L. (1990). Too scared to cry. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Wood, M. M., & Long, N. J. (1991). Life space intervention: Talking with children and youth in crisis. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed, Inc.