Motivation

The desire of parents and teachers is to have every student exhibit the traits of intrinsic learners-students who arrive ready to learn, actively participate, and strive for excellence. Over the years professionals and parents have discussed self-esteem, various behavioral approaches to facilitating motivation, and have applied countless strategies to poke and prod reluctant learners into submission. Among the strategies commonly tried are sticker charts, payment for work completion or grades, the removal of desired objects or activities such as cell phones or football practice contingent upon the demonstration of desired behaviors and finished assignments. Certainly, the cause and effect with regard to effort and results needs to be modeled and taught. Likewise, if a young person is too distracted or busy to focus on school achievement, something will need to be done to minimize demands on the young person's time and attention. Unfortunately, we adults miss the forest for the trees in attempting to understand and respond effectively to the less than enthusiastic learners we encounter. Telling a student that he or she is smart or talented might help to make the student feel better momentarily, but such shallow responses to self-esteem building are hardly going to make a dent in the heart and mind of a young person who struggles to read, write, or compute.

Instead of developing a sticker chart, heaping praise on a weary academic warrior, or enforcing aversive consequences, it is much more helpful to take a look at the factors impacting a particular student or group of students. A few anecdotes from personal experience might be of help as an illustration.

A young lady I will call Jenny to protect her identity absolutely refused to work with fractions. She had struggled for 3 years and had decided that she was dumb. Although there were many signs that Jenny was far from dumb given her above average command of spoken language, she just couldn't wrap her head around the idea that she was bright. Teachers and parents had praised her, offered privileges and desired items for work completion, and taken away desired items and privileges for refusal to work. She had had enough. She was done with all of their games. Allowing her to sit day after day in sullen silence was not an option. She needed to learn to understand and compute fractions. Even more than that, she needed to discover how truly capable she was as a learner. I took the math book away from her and told her that she would not be in a math group--that we were going to try something different. She liked that idea and was willing to give the new plan a try. I explained to her that we were going to work with colors for awhile-no numbers-no fractions-just colors. Jenny wanted to be a fashion designer when she was older and loved the idea of using different types, textures, and colors of paper. For 3-4 days she cut wallpaper samples into rectangles as directed and placed them in an inexpensive plastic frame, answering questions such as "How many pinks equal a green?" When she began to complain that the tasks were too easy, I revealed that she had been doing fractions. The green represented 1 whole. The pink pieces represented 1/2, etc. She happily labeled the pieces and was able to see how equivalent fractions worked, why unlike fractions had to be converted to like fractions before completing computation, as well as, the hows and whys of improper fractions. By the end of the week, Jenny had caught up with her peers conceptually. Her motivation problems were related to her confusion over a concept that she did not understand. She was not being defiant, she was confused.

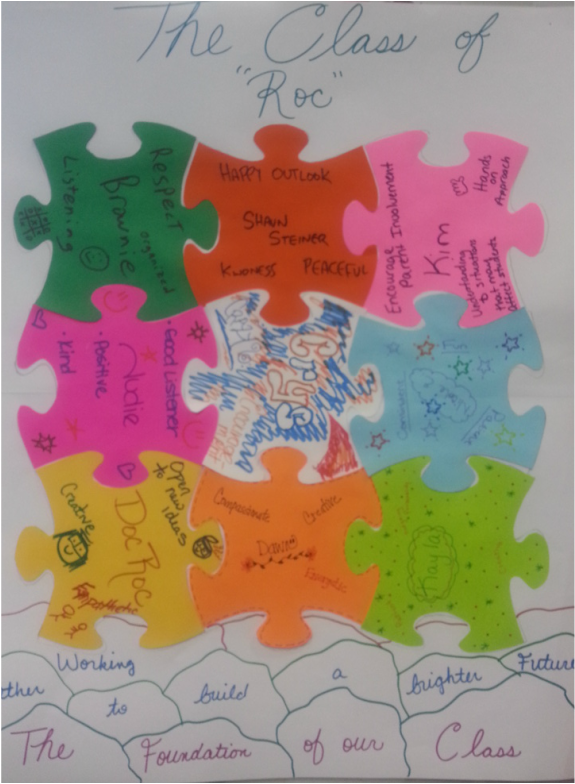

The puzzle pictured above was constructed by a group of university students during a community-building activity. Some students are more motivated to achieve and participate when they are part of a team. Allegiance to a team effort, the need to save face among peers, or the camaraderie of a collaborative group can motivate students more powerfully than individual forms of reinforcement.

Another group of students with whom I worked hated reading. They would cry, throw books, and dive under tables when it was time to read. I removed all reading books from sight. We played games with sight words and matched picture cards with common nouns. Students colored bar charts in their data folders to record how many words they had learned. As a student mastered all of the words in a small story book, I would hand the student a copy saying. "You already know all of the words in this book. I thought you might enjoy reading it." Successes built upon successes until we were actually able to have a class library, engage in typical reading lessons, and deal with the minor frustrations of the learning process.

One additional example of motivation challenges occurred with a group of middle school students who had been highly productive and cooperative and suddenly began to resist learning tasks and engage in frequent arguments. The teacher couldn't put her finger on what had precipitated the change. We talked. As we identified the week when the atmosphere in the room began to change, the teacher realized that a change in schedule had occurred. Students were going to lunch 45-60 minutes later due to school-wide scheduling changes that were made to accommodate the physical education class schedules. When the teacher implemented a healthy snack policy, learning and behavior problems subsided. It is likely that behavior charts, rewards, and punishments would not have had the desired effects. Students who are hungry are not going to be as motivated and cooperative as teachers and parents would prefer. Please access the free downloadable handout on motivation posted below. You will identify various sources of motivation within individuals and groups. By broadening our understanding of motivation, we are better equipped to pinpoint needs of learners and design an effective plan.

The desire of parents and teachers is to have every student exhibit the traits of intrinsic learners-students who arrive ready to learn, actively participate, and strive for excellence. Over the years professionals and parents have discussed self-esteem, various behavioral approaches to facilitating motivation, and have applied countless strategies to poke and prod reluctant learners into submission. Among the strategies commonly tried are sticker charts, payment for work completion or grades, the removal of desired objects or activities such as cell phones or football practice contingent upon the demonstration of desired behaviors and finished assignments. Certainly, the cause and effect with regard to effort and results needs to be modeled and taught. Likewise, if a young person is too distracted or busy to focus on school achievement, something will need to be done to minimize demands on the young person's time and attention. Unfortunately, we adults miss the forest for the trees in attempting to understand and respond effectively to the less than enthusiastic learners we encounter. Telling a student that he or she is smart or talented might help to make the student feel better momentarily, but such shallow responses to self-esteem building are hardly going to make a dent in the heart and mind of a young person who struggles to read, write, or compute.

Instead of developing a sticker chart, heaping praise on a weary academic warrior, or enforcing aversive consequences, it is much more helpful to take a look at the factors impacting a particular student or group of students. A few anecdotes from personal experience might be of help as an illustration.

A young lady I will call Jenny to protect her identity absolutely refused to work with fractions. She had struggled for 3 years and had decided that she was dumb. Although there were many signs that Jenny was far from dumb given her above average command of spoken language, she just couldn't wrap her head around the idea that she was bright. Teachers and parents had praised her, offered privileges and desired items for work completion, and taken away desired items and privileges for refusal to work. She had had enough. She was done with all of their games. Allowing her to sit day after day in sullen silence was not an option. She needed to learn to understand and compute fractions. Even more than that, she needed to discover how truly capable she was as a learner. I took the math book away from her and told her that she would not be in a math group--that we were going to try something different. She liked that idea and was willing to give the new plan a try. I explained to her that we were going to work with colors for awhile-no numbers-no fractions-just colors. Jenny wanted to be a fashion designer when she was older and loved the idea of using different types, textures, and colors of paper. For 3-4 days she cut wallpaper samples into rectangles as directed and placed them in an inexpensive plastic frame, answering questions such as "How many pinks equal a green?" When she began to complain that the tasks were too easy, I revealed that she had been doing fractions. The green represented 1 whole. The pink pieces represented 1/2, etc. She happily labeled the pieces and was able to see how equivalent fractions worked, why unlike fractions had to be converted to like fractions before completing computation, as well as, the hows and whys of improper fractions. By the end of the week, Jenny had caught up with her peers conceptually. Her motivation problems were related to her confusion over a concept that she did not understand. She was not being defiant, she was confused.

The puzzle pictured above was constructed by a group of university students during a community-building activity. Some students are more motivated to achieve and participate when they are part of a team. Allegiance to a team effort, the need to save face among peers, or the camaraderie of a collaborative group can motivate students more powerfully than individual forms of reinforcement.

Another group of students with whom I worked hated reading. They would cry, throw books, and dive under tables when it was time to read. I removed all reading books from sight. We played games with sight words and matched picture cards with common nouns. Students colored bar charts in their data folders to record how many words they had learned. As a student mastered all of the words in a small story book, I would hand the student a copy saying. "You already know all of the words in this book. I thought you might enjoy reading it." Successes built upon successes until we were actually able to have a class library, engage in typical reading lessons, and deal with the minor frustrations of the learning process.

One additional example of motivation challenges occurred with a group of middle school students who had been highly productive and cooperative and suddenly began to resist learning tasks and engage in frequent arguments. The teacher couldn't put her finger on what had precipitated the change. We talked. As we identified the week when the atmosphere in the room began to change, the teacher realized that a change in schedule had occurred. Students were going to lunch 45-60 minutes later due to school-wide scheduling changes that were made to accommodate the physical education class schedules. When the teacher implemented a healthy snack policy, learning and behavior problems subsided. It is likely that behavior charts, rewards, and punishments would not have had the desired effects. Students who are hungry are not going to be as motivated and cooperative as teachers and parents would prefer. Please access the free downloadable handout on motivation posted below. You will identify various sources of motivation within individuals and groups. By broadening our understanding of motivation, we are better equipped to pinpoint needs of learners and design an effective plan.

| motivation_handout_2.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1266 kb |

| File Type: | |

| motivation_plan_template.pdf | |

| File Size: | 65 kb |

| File Type: | |